A Tribute to My Father

By Vivian Emmeline Stanton Fraser

Thorold, Ontario, February 26, 1969

He is gone. We buried him today. Under bright sunny skies on a late March day, we followed him up the hill to his last resting place. Beneath the whispering pines, his mortal remains were lowered into the good earth beside those of our mother who left us long years ago. This was a different sort of sadness today. A strong undertow of pride and satisfaction in a good, full, long life, rich in achievement and kindly deeds, surged beneath our tears for our own loss.

No headlines in the papers, but a great wave of tributes from near and far swelled as the news of his passing spread. He had that rare gift of communication with young and old, and his spirit seemed ageless. So it came as a shock to see him lying there, an old man of ninety—the shining spirit departed.

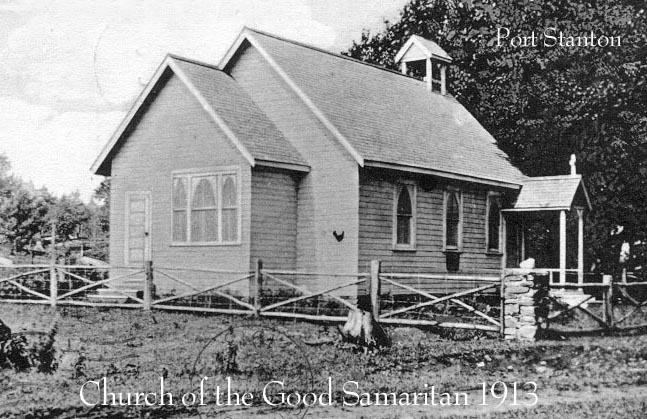

He reached out in so many directions, whether towards a visiting official from the big city or a very small great-grandson having trouble with his wagon. Although in later years he mellowed, his youth was filled with impatience. So much to be done, and he did it! Born in a pioneer time, there were virgin woods to be cleared and a home to be built. Although the construction of a log school and the hiring of a teacher for $250 dollars a year meant the provision of a basic education, this man’s pursuit of knowledge did not stop there. He studied books and took courses, and learned how to do many things by just doing it. He served on the school board for many years, and he advanced with the times. A church was needed, and as no real roads existed, lumber and planks were floated down the river from the nearest mill and a small church was built, which was not large enough for his funeral today.

A railway was needed and family land given to provide a right of way. Indeed the house itself had to be moved some hundred feet toward the lake, and we grew up so close to the track that we never noticed the rumble of trains that disturbed overnight visitors. As more families became established along the shores of Sparrow Lake, a post office was needed, and my father became the first postmaster of Port Stanton, a position he held for nearly forty years.

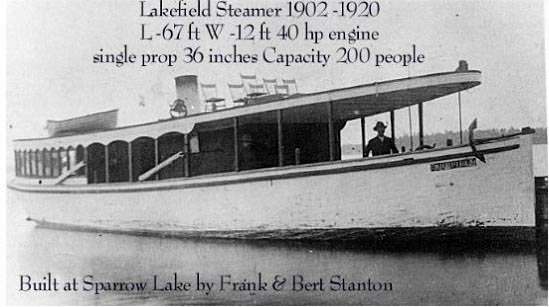

Boats were essential in those early days. With his brother Albert he constructed a steamboat seventy feet long, the “Lakefield,” able to carry two hundred passengers. Early memories are of Dad in his captain’s hat at the wheel, and a pile of wood slabs on the deck for fuel. On May 24th each year, family and friends were taken by the steamer for an all-day picnic to Deep Bay Point.

By now, tourists were coming into the area, including many fishermen. The brothers started up a sawmill that provided lumber for homes and cottages as well as giving work to young men. As the number of summer visitors to our lake increased, there were many cottages to be built, and my father used to skate across the ice and construct buildings for the wage of one dollar a day. On Sundays he would take Mother and one or two of the small children on a homemade sleigh and pull them as he skated about the wide expanse of ice. In summer he would use a canoe, and he paddled with short powerful strokes. Mother must have had great faith in him, because she could not swim.

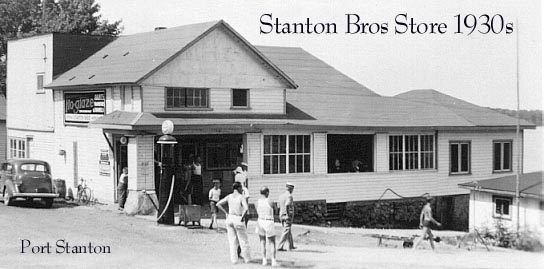

The frozen lake provided the refrigeration needed by residents as well as cottagers. This busy man organized an ice company that cut the blocks of ice in the winter, at first with a crosscut saw and later on one driven by gasoline engine. These blocks were hauled by team and sleigh to all points of the lake, stored in icehouses and packed in sawdust from the mill. A general store was built and became a hive of activity. Groceries, ice-cream parlour, boat rental, bait, magazines, running-shoes, drug needs, kerosene, ice and many sundry items were all part of the business, which became known as Stanton Brothers store.

Never much of a farmer himself, my father saw that the family had the usual necessary animals and a big garden. He owned a pair of oxen, Buck and Bright, and the marshes provided the hay. There was a time when a venture was taken into sheep raising, but it seemed more of a disaster than anything else. There were not many fences, and the forest was close enough for sheep to wander away. We owned cows, but I don’t remember Dad doing the milking. Always there were more pressing things for him to do, and to the children fell the job of “getting the cows” each late afternoon.

The home became equipped with various conveniences, perhaps a decade or two ahead of common usage. Gas lighting was installed, for which we had a carbide-burning plant in the basement. From time to time it made ominous noises and we were told to run outside as it might blow up. I often wonder how we escaped major fires with those gas pipes that ran along the walls and jets that were lit with a match. Then there was hot-water heating–a big old homemade furnace, an assortment of pipes, and boilers of various sizes in our rooms. There was a hot-water tank lying on its side by our bed. It was nice to put our long winter underwear on, but it used to make fearful sounds.

We always had some sort of water supply in the house. My earliest memories are of a system that used an open tank in the attic and a gasoline engine in the ceiling. There was an overflow pipe and a bell, so that by listening and watching out the window, one knew when to shut off the pump. Sometimes there were accidents. A powered washing machine was another of his ideas. No doubt it helped reduce the workload, but the basement laundry area was pretty well filled with two big rinse tubs and the washer attached by a long pulley to a gas engine that had to be started up for each load.

Later when cars came into use and roads were opened up, he rigged a snowplow to attach to the car so that the snows of winter never kept him home. He was never happier than when seeing an idea come to fruition, and he built a snowmobile when they were a real novelty.

As the years passed, he became more interested in growing things and he built a greenhouse. A brief excursion was made into the propagation of mushrooms, but I cannot remember eating any, and this venture was given up. However, the greenhouse provided pleasure, and we always had a great supply of lettuce, radishes and green onions.

Quick to see a chance to profit by some undertaking, he was yet so honest that I have never even now learned to be sceptical about other people. He believed that one should not owe money overnight and always seemed to have his pouch purse out to pay off a workman at the end of each day. Blessed with tremendous vitality and good health, he took good care of himself. His morning bath was an absolute must, and he always shaved before coming to breakfast. His faith in God was an intrinsic part of his life, but he was not given to discourse on religion. He loved music and especially the hymns of the church. His idea of a good time was to have a gathering around the piano with singing and two or three violins playing. He himself played the violin by ear, and he had a good singing voice.

He loved the country life and the lake. Piloting his boat, be it large or small, was one of the big joys of his career. When he finally had to give that up, well after his four score years, something vital was lost. In early spring, he always had the urge to dig for crinkleroot in damp places, and to search for watercress in the fresh-running creeks. We learned from him where to find the crumply morels under the pine trees when the warmth and humidity were just right to bring them up overnight. His annual holidays usually meant nights in a launch tied up along a quiet waterway or under canvas. In later years, he contented himself with short motor trips, sleeping in a cabin but always eating outside.

Making maple syrup was an early spring joy in our life as children. Dad would build a firebox of bricks and surmount it with a rectangular tin pan. A barrel with a pipe and tap was supported at one side of the evaporator. Into this barrel we would dump the pails of sap as we gathered it, and we had a share in skimming the boiling liquid and stuffing wood into the fire. We had fun, staying in the woods for lunch, boiling eggs in the hot sap and making sap coffee. We usually were allowed to boil some syrup a little extra, beat it and pour it out on clean snow for taffy in fancy shapes.

The family was the main thing. Frank Stanton wanted as many as possible to settle in the immediate vicinity. He saw that all the children got an education and a chance to make their way. Later when some lived at distant points, he always sent invitations to come home for festive occasions. Christmas was made such a happy time when we children were small. Dad used to don a Santa Claus suit and bring our filled stockings to us in our beds. There were sometimes hoof marks in the deep snow on the lawn and even on the roof. Sometimes we even heard the sleigh-bells from the reindeer. During the long sleepless Christmas Eve when we children were trying to get to sleep, Dad was busy in the kitchen making great bread pans of peanut brittle. Sometimes he scorched a batch that we had a hard time to eat up.

Hospitality was a way of life to him. Always in the early days of our church, it seemed that the minister had to sleep overnight at our place. On Sundays, any extra people at church got invited to come home for dinner, and a few more boards would be fitted into the long table. The Sunday roast was bountifully served to the first lucky people, and the children watched as the last servings got smaller and smaller.

Frank Stanton had a strong personality. He lived by a stern code of ethics and wanted others to do likewise. All issues were black and white to him, especially in his vigorous years. But while many may have disagreed with his views, all had to respect him and felt the impact of his being. In the midst of such rapid change and progress today, a backward glance provides context and continuity. Perhaps never again can one man’s life span such a period between simple pioneer days and the complex modern life. It is the end of an era.